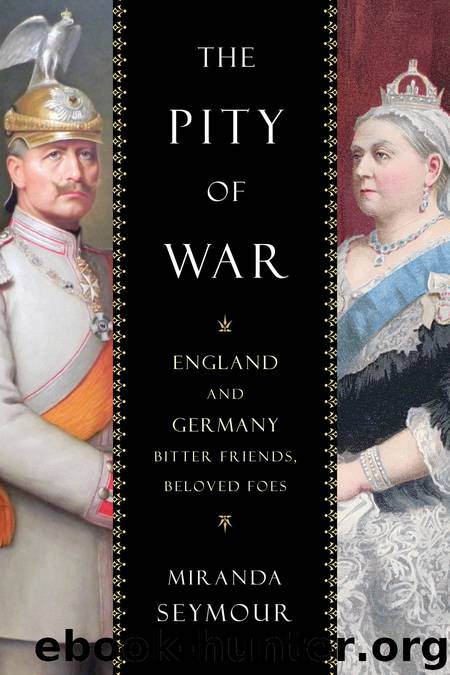

The Pity of War by Miranda Seymour

Author:Miranda Seymour

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781442241756

Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

PART TWO

From Versailles to the Verge of War (1919–40)

18

LOVE AMONG THE RUINS

(1919–23)

The challenge facing the modest and quietly spoken Friedrich Ebert as the first president of Germany’s new Weimar Republic was considerable. In 1920, the President was briefly deposed during a right-wing coup supported by Erich Ludendorff, an embittered general who dreamed, ahead of Hitler, of a vastly expanded Germany, filled with soldiers and emptied of Jews. In 1922, it was Ebert’s task to calm the country after anti-Semitic right-wingers assassinated, in open public view, Germany’s foreign minister, Walther Rathenau. (Rathenau, a remarkable man, was the nephew of one of Germany’s greatest artists, Max Liebermann.) In 1923, Ebert and Gustav Stresemann, his able and intensely Anglophile new Chancellor, struggled to retain control during the terrifying inflation surge, when family fortunes were destroyed overnight and when Germany faced starvation for a time. President Ebert faced a challenge of a different order in the November of that year when Adolf Hitler embarked on his first attempt to seize power for the emerging Nazi party, in a Republic where support for the right remained strong and the swastika was already becoming a familiar symbol of the union, in wavering times, between firm conviction and brute force.

Hitler’s name was still unknown back in the Berlin of 1920, where a twenty-year-old Hansel Pless was studying for his law exams. Up at the family homes of Fürstenstein and Pless, a dinner jacket remained essential attire even for a quiet supper alone with the ageing Prince Heinrich, while a ventured remark about powder-headed footmen being just a little out of date could lead to a growl of contempt for such ‘Bolshevik’ notions. In Berlin, Hansel found lodgings with a hard-up widow (‘a very kind and intelligent Jewess’) whose brilliantly academic sons, when not entertaining Professor and Mrs Einstein to tea, cordially addressed each other across the table as ‘You so-and-so Jew’. Hansel, while initially startled, decided that he preferred such directness to the ornate courtesies required at Pless.1

Hansel was a young man who took life as it presented itself. He didn’t consider it especially odd that a young man whose family castle had served as the eastern headquarters of the German Army was welcomed, during his time in Berlin, as a daily visitor to the British Embassy. Here, when no official event was in progress and no legal lectures required Hansel’s attendance, Lord D’Abernon and his guest passed the time by playing badminton in the vast and chilly ballroom, pausing only when Ribbentrop, the Ambassador’s obsequious wine merchant, paid an unscheduled visit and, unwanted, lingered on.

As the half-English son of a German prince, Hansel took his own welcome on the Wilhelmstrasse for granted; later, he came to appreciate that Lord D’Abernon’s friendly manner had been part of a general endeavour to help the cause of reconciliation. Recalling his years at the Embassy in Berlin in 1929, at a time when Germany faced a new financial crisis, Edgar D’Abernon urged readers of his memoirs to forget the past and to treat Germany ‘as a great power and not as an outlaw’.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Arms Control | Diplomacy |

| Security | Trades & Tariffs |

| Treaties | African |

| Asian | Australian & Oceanian |

| Canadian | Caribbean & Latin American |

| European | Middle Eastern |

| Russian & Former Soviet Union |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18998)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12177)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8874)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6856)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6248)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5765)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5716)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5481)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5409)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5200)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5130)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5065)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4937)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4899)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4758)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4727)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4684)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4486)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4473)